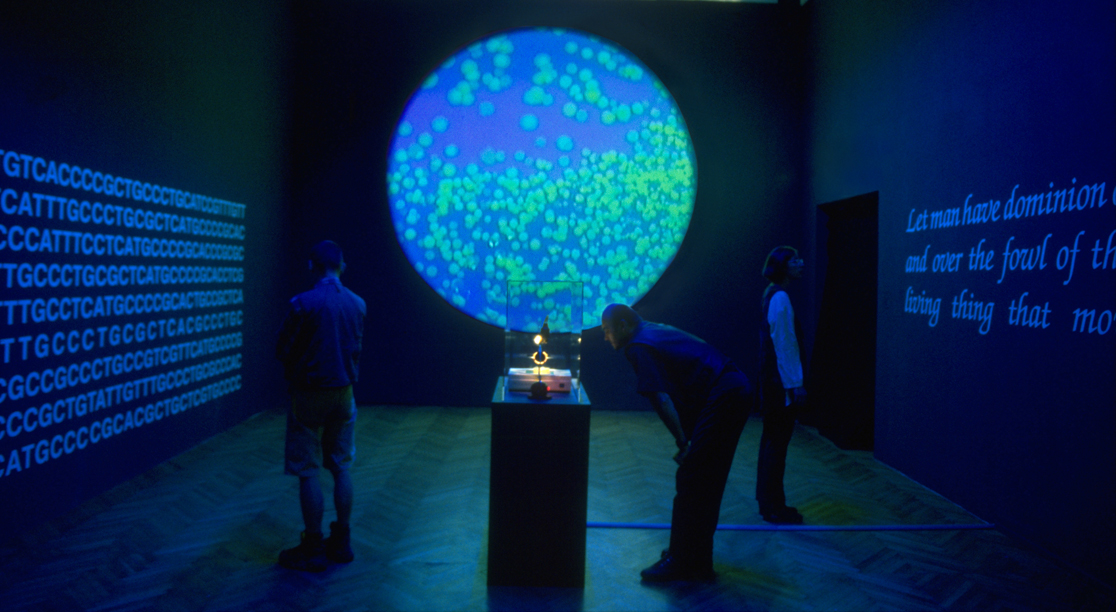

Photo: Courtesy of Julia Friedman Gallery, Chicago

ART CREATING LIFE: Eduardo Kac's Genesis project enables

viewers to create bacteria mutations.

A stroll through an art museum can mirror a walk outdoors, as nature

has inspired artists since people first used charcoal to draw on cave

walls. Today, ambitious artists and accessible technologies have

modernized the marriage of biology and art into bioart, coupling

imagination and science to create animate, often interactive, works

that put pretty paintings of flowers to shame.

"[Bioart's popularity] is similar to the video movement in the arts,"

says Ruth West, lecturer at the University of California, Los Angeles.

"Before, you'd have to go into a television station for access to video

equipment. Now you can walk into a Best Buy [store] and get an

incredibly powerful camera." While most students will never have

their own DNA sequencer, the recent biotechnology boom is

providing a greater opportunity to incorporate science into art.

A new understanding of perspective gave Renaissance artists their

inspiration, and the emerging science of optics informed the work of

the Impressionists in the late 19th century. Today molecular biology

techniques and tools allow a new generation of artists to transform

the art world, once again. "I have an interest to use the tools of my

time to tackle certain issues, which is something artists have always

done," says artist Eduardo Kac.

As new as the technologies that make it possible, bioart first

emerged as explorations by science students and practitioners. But it

has moved into the mainstream as established galleries such as the

Museum of Modern Art in New York City and the Corcoran Gallery of

Art in Washington, DC, have exhibited live works.

Last week, the Corcoran opened the exhibit, Molecular Invasion, by

members of the Critical Art Ensemble, an interactive theater

company, which plans to display the creation of a genetically

modified plant as part of the exhibition. Such scientific capabilities

create new moral problems--which have always been the purview of

painters and sculptors. "Many people perceive themselves as

separated from science because it's too complex," says Paul

Brewer, director of college exhibitions for Corcoran College of Art.

"Bioartists try to demystify the scientific process so they can engage

with the ethical issues at stake."

TRANSCENDING CLICHÉ WITH TRANSGENICS Even though Kac

lacks experience with the scientific process, he appears more

comfortable with transgenics than with paintbrushes. Inspired by a

passage from the Bible, in which God gives man control over earthly

creatures, Kac's Genesis project bestows godlike power to

humanity on a microscale. For Genesis, Kac translated a line of

biblical text into Morse code, then encoded it into DNA and inserted it

into bacteria, which are displayed on a microscopic slide in a

darkened room.

This installation, which can also be accessed online,1 allows the click

of a computer's mouse to focus ultraviolet light on the display,

causing mutations in both the bacteria's genome and in the coded

message. "The metaphor of art imitating life doesn't apply anymore,"

Kac says. This is a situation where art is creating life."

While Kac allows Genesis participants to play god across oceans,

Joe Davis, research affiliate at the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology (MIT) is trying to apply his art over an even greater

distance. Using the durable Escherichia coli as a vessel to weather

the harsh climate of space, he coded an image of the Milky Way into

a 3867-amino acid long sequence, inserted it into the bacteria's DNA,

and hopes to launched it out in the cosmos. "It's true genomic art,"

Davis says. "I was able to write underneath an existing gene

without changing the [mRNA] transcript. It doesn't interfere with the

organism at all."

Quick to dismiss formal artistic landscapes as tedious and restrictive,

Davis continues his unconventional craft; his fascination with both art

and science has proven more beneficial to him than could a formal

background in either discipline. "I have no classical credentials in

science, and an appointment at MIT Biology that doesn't say

anything about art," says Davis.

Davis' lack of background has not kept him from breaking ground

where science meets art. He first showed that DNA could encode

other types of information (not just genetic sequences) in 1986 with

Microvenus, where DNA was first used as an artistic medium. Davis

digitized the Microvenus icon, translated it into a 28-nucleotide

chain, and inserted it into the genome of E. coli.

Microvenus, which looks like the letter Y superimposed upon the

letter I, is a Germanic rune representing life and the outline of the

external female genitalia. Davis created the icon as a way to show

symbols of human intelligence to extraterrestrial beings.

The bacteria have since multiplied into billions of cells, and Davis

reckons that Microvenus is more abundant than all artworks by all

previous artists. Still, Microvenus has yet to be on display in the

United States, because galleries are reluctant to display genetically

engineered bacteria.

TRADITION AND TECHNOLOGY Not all bioart is as conceptual as is

Davis' work. Heather Acroyd and Dan Harvey of Dorking, Surrey,

UK, take photographs and record the images through the production

of chlorophyll in grass. The yellow and green shades of grass create

the tonal range of a black-and-white photo. The idea emerged when

the artists noticed an area of grass that produced the shadow of a

ladder leaning against it. They projected a high intensity light

through a photographic negative onto a canvas covered in clay and

grass seedlings, and formed a yellowish image.

The problem for Acroyd and Harvey was that as the grass faded, so

did their exhibits. The photographers contacted the Institute of

Grassland and Environmental Research (IGER), in Aberystwyth,

Wales, which had been working on a grass hybrid that doesn't lose

its color. "Our 'Stay Green' grass can't break down its chlorophyll, so

the images stay sharp," says Helen Ougham, principal research

scientist at IGER. Despite the use of hybrid seeds and blades, the

images are still vulnerable to oxidative bleaching, making them as

transient as the living beings they record.

Bioartists sometimes require scientists to assist with technical

procedures that enhance the creative process. Hunter O'Reilly,

adjunct professor of biological sciences, University of Wisconsin,

Milwaukee, received her introduction to art through sciences while

taking the "wrong path on the road to discovery" during her

graduate studies in genetics.2

A visit to Paris art museums inspired O'Reilly to escape her scientific

studies through art. "But cellular forms started to evolve in my

paintings," she says. Today O'Reilly uses deadly viruses like Ebola

and AIDS to create pictures. She also teaches a class, "Biology

Through Art," that integrates both disciplines. "The biology is pretty

general, but I also teach how some of my contemporaries work

biology into their art."

For her course, "Genetics and Culture," UCLA's West gathers

students from all corners of the campus. "There is a certain phobia

between art and science, because they've been separated for so

long," West says. Her students critique the artwork, analyze the

science, and evaluate the ethical and cultural implications of the new

techniques.

An artist sometimes featured in West and O'Reilly's classes, Gunther

Von Hagens has come under fire for his innovations. Von Hagens,

director of the Plastination Centre at the State Medical Academy in

Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, invented plastination, a preservation technique

that replaces the water in cells with a polymer, rendering the corpse

odorless, dry, and realistic looking. The displays give some viewers

new respect for their bodies; a smoker's lung or cholesterol-clogged

arteries can be viewed as they would appear inside the human body.

The macabre exhibitions have led many others, however, to dismiss

Von Hagens as a modern-day Dr. Frankenstein, according to The

Guardian.3

Kac also has caused such a stir in both art and science spheres a

few years earlier with his Alba project. Kac inserted genes for

fluorescence into a rabbit, generating a green, glow-in-the-dark

bunny when exposed to blue light at 488 nm. "There was a semantic

tension," Kac says. "Bringing together a symbol of cuteness, like a

rabbit, and transgenics, which resonates with fear and the unknown,

is not a simple juxtaposition."

These artists don't try to be didactic; they simply want to present

everyday objects in a new light. "In a way, art is like science," Davis

asserts. "Art opens up little windows onto the world that nobody has

ever seen before. I get a kick out of opening those windows."

Hal Cohen can be contacted at hcohen@the-scientist.com.

References

1. The Genesis interface is available online at www.ekac.org/liveinfo.html.

2. H. Cohen, "Life posing as art," The Scientist, 16[19]:8, Sept. 30, 2002.

3. S. Jeffries, "The naked and the dead," The Guardian, March 19, 2002,

available online at www.guardian.co.uk/g2/story/0,3604,669775,00.html.

©2002, The Scientist Inc.