Originally published in Kostic, Aleksandra (ed.). I Levitate, What's Next... (Maribor, Slovenia: Kibla, 2001), pp. 88-97. Updated and republished in French and English in: Space Art, A. Bureaud, J.-L. Soret (dir.), catalogue du Festival @rt Outsiders 2003, numéro spécial, Anomos, Paris, sept. 2003, pp. 196-199. Also published in Tate in Space, 2003 <http://www.tate.org.uk/space> and Art Catalysts, 2003 <http://www.artscatalyst.org>. Updated and republished in : Zero Gravity: A Cultural Users Guide (London: The Arts Catalyst, 2005), pp. 18-25. Published in German as: "Gegen den Gravitropismus", Der Freund, N. 4, Sept. 2005, Hamburg, pp. 80-88.

AGAINST GRAVITROPISM: ART AND THE JOYS OF

LEVITATION

Eduardo Kac

"Gravitropism" means growth in response to gravity [1]. I

use the term gravitropism in art beyond its biological

origin, to underscore the fact that gravity plays a

fundamental role in the forms and events we are able to

create on Earth, and that forms and events created in zero

gravity to be experienced in the same environment might be

radically different. Gravity is the weakest known force, but

is the most evident in our everyday life. While great minds

have tried to understand it, from Galileo and Newton to

Einstein and Hawking, it still remains fundamentally

unclear. And while its reconciliationt with quantum

mechanics is a remit of modern and contemporary physics, it

has been largely marginal in modern and contemporary art. I

first wrote about gravitropic forms and events in 1987,

while creating and articulating the theory of a new poetic

language produced out of light, with protean linguistic

events floating and changing in space, freed from material

and gravitational constraints. In my original text I stated:

"As we experience massless optical volumes -- focused

luminous vibrations suspended in the air -- "gravitropism"

(form conditioned by gravity) makes way for

"antigravitropism" (creation of new forms not conditioned by

gravity), freeing the mind from the clichés of the physical

world and challenging the imagination". [2] I coined the

word "antigravitropism" to retain the affirmative quality of

negating or neutralizing gravity.

The powerful gesture of defying gravity in art can be traced

back to innovative early twentieth-century sculptors, such

as Calder and Moholy-Nagy. While the first reduced the

support of massive structures to a single suspended point

with his "Mobiles", the second went as far as experimenting

directly with levitation, with absolutely no physical

support whatsoever. In his seminal book "Vision in Motion",

published posthumously in 1947, Moholy-Nagy appears

levitating a chisel with compressed air. The photograph is

striking: we see Moholy-Nagy's profile and before him the

object suspended in the air with no apparent means of

support. In previous books Moholy-Nagy articulated notions

about the evolution of sculptural form, suggesting that the

virtual volume--volume created optically by the accelerated

motion of an object--was a new possibility for sculpture. In

his film "Design Workshops" (1946), he presented a sequence,

less than a minute long, in which colored ping pong balls

float in an air jet. As an artist crossing many discipline

boundaries, Moholy-Nagy also considered that in the future

the neutralization of gravity could be a useful tool in

design. It was not until the 1960s that several of this

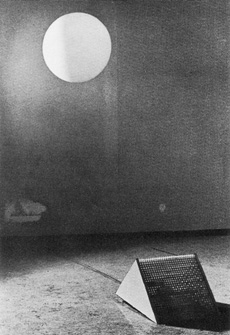

visionary's ideas would find currency. Hans Haacke's

sculpture "Sphere in Oblique Air-Jet" (1967), presents the

viewer with precisely what its title indicates: a buoyant

balloon that stably hovers in space. The sculpture

accomplishes this feat through what is known as Bernoulli's

principle, according to which a stream of air (or fluid) has

lower pressure than stationary air (or fluid). On a

practical level, this means that moving air can create

aerodynamic lift.

|

|

|

| Moholy-Nagy levitating a

chisel, as reproduced in "Vision in Motion", 1947. Courtesy Hattula Moholy-Nagy |

Hans Haacke, "Sphere in Oblique Air-Jet", 1967. |

Although the Hungarian constructivist did not explore this

notion in his own sculptures, levitation and the conquest

of space attracted the attention of artists working in the

1950s. Lucio Fontana's Spatialist movement, for example,

made direct references to space. In 1951 he clearly

stated: "Man's real conquest of space is his detachment

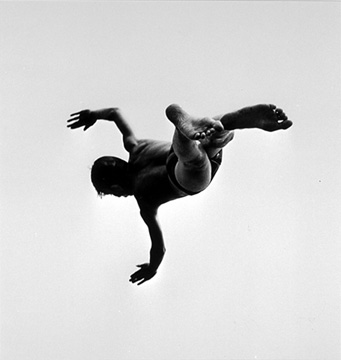

from the earth". Aaron Siskind's 1950s series of

photographs "Terrors and Pleasures of Levitation" present

the viewer with contorted and airborne human bodies. These

compelling images, which evoke humankind's mythical dream

of flying, look as though they could be right out of an

astronaut training program. While in both cases it is

really the metaphor of space and levitation that is

brought to the fore, the use of magnetism to suspend forms

in space became the key element in the innovative work of

the Greek kinetic artist Takis. In 1938 Gyorgy Kepes

produced a series of photographs and photograms in which

he experimented with the visual properties of magnets and

iron filings, but it was Takis who, in 1959, introduced

the aesthetic of sculptural magnetic levitation with his

elegant "Télésculpture". The sculpture is composed of

three small conical metal pieces that are attached,

through thin wires, to three nails. The three conical

pieces are suspended above an irregular plane and levitate

in front of a magnet. This was the seed of a complex body

of work through which this magician of levitation has

investigated the expressive power of invisible forces. In

September of 1959, the Moon was first visited by the

Soviet spacecraft Lunik 2. As the first probe to impact

the Moon, Lunik 2 made evident that human displacement in

space was on the horizon. Fascinated by the implications

of this idea, Takis realized an event in 1960 at the Iris

Clert Gallery, in Paris, entitled "L'Impossible, Un Homme

Dans L'Espace" (The Impossible, A Man in Space). Donning a

"Space Suit" designed by Takis, wearing a helmet, and

attached to a metal rod connected to the floor, Sinclair

Belles was "launched" across the gallery onto a safety

net. The event orchestrated by Takis pointed to the

unknown: the logic and the biologic that govern human

existence on Earth will not readily apply to our life in

space. Also responding to the visual and intellectual

stimulation provided by humankind's first steps beyond the

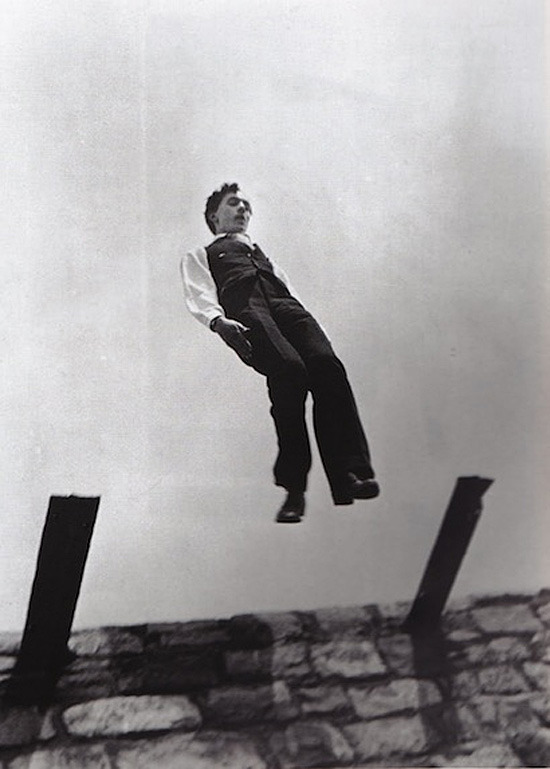

Earth, Yves Klein's "Leap into the Void" (1960) was a

photomontage alluding to the new condition of the body

considered, rather concretely, in relation to the cosmos

(reminiscent as it was of Siskind's series). It is worth

noting that other artists active in the 1960s further

elaborated the vocabulary of magnetism. Harvard-educated

Venezuelan sculptor Alberto Collie created electromagnetic

levitators for innovative sculptures called spatial

absolutes. In his sculptures he employed titanium disks

that float freely (that is, with no point of attachment)

in an electromagnetic field. If the disk budges, a

feedback system strengthens the field, thus keeping the

disk in its state of equilibrium.

|

|

|

||

| Yves Klein, "Leap into The Void" (1960), Silver gelatin print, 350 x 270mm. |

Aaron Siskind, "Terrors and Pleasures of

Levitation, No. 37" (1953), gelatin silver print,

25.1 x 24.1 cm., collection George Eastman House. |

Jacques Henri Lartigue, Zissou, Rouzat, 1908 |

Partially inspired by the incipient space program, the

utopian architecture of the 1960s yielded visions of

floating communities hovering among the clouds.

Buckminster Fuller and Shoji Sadao created such a

concept, entitled "Project for Floating Cloud Structures

(Cloud Nine)." Fuller's imaginary floating

sphere-enclosed cities are given a sense of feasibility

through technical explanations that would seem to render

them possible. The visionary architect drafted plans in

the early sixties for spheres

that would hover above the earth

and hold several thousand "passengers."

|

| Buckminster Fuller and Shoji Sadao project for "Floating Cloud Structures (Cloud Nine)", ca. (1960). Black-and-white photograph mounted on board. 15 7/8 x 19 3/4 in. (40.3 x 50.2 cm). |

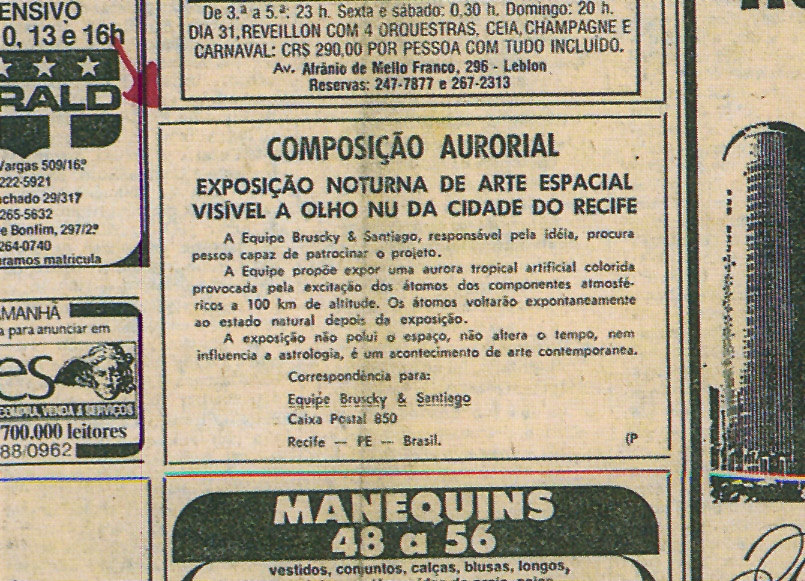

One peculiar approach to the suspension of (ephemeral) forms in space is the use of vaporous substances through a technique known as Skywriting, which consists in the writing or drawing formed in the sky by smoke or another gaseous element released from an airplane, usually at approximately 10,000 feet. In the late 1960s and early seventies, artists such as James Turrel, Sam Francis, and Marinus Boezem started to employ skywriting as a medium. Poet David Antin created skypoems over Los Angeles and San Diego in1987-1988. These and other artists and writers created evanescent forms within what is known as troposphere, that is, the lowest atmospheric layer. Pushing the concept of a sky art into the space age, beyond aerial acrobatics and the design of evanescent forms, the Brazilian artist Paulo Bruscky proposed, in 1974, the creation of an artificial aurora borealis, which according to the artist would be produced by airplanes coloring cloud formations. Bruscky published ads in newspapers to both document the project and inform the public. The ads were also an instrument in his search for sponsors. They were published in the Brazilian papers Diário de Pernambuco, in Recife, September 22, 1974 and Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, December 29, 1976. While on a Guggenheim fellowship in New York, he also published ads in the Village Voice, New York, May 25, 1982. The creation of artificial auroras was realized in 1992, not by Bruscky, but by NASA as part of environmental research. Approximately sixty artificial mini-auroras were created by employing electron guns to fire rays at the atmosphere from the space shuttle Atlantis. The sky was also the environment of "Searchlight", an artwork created by Forrest Myers in 1975. Myers used four carbon-arc searchlights and made them converge to a point above Artpark, Lewiston, New York. This light sculpture created the form of a pyramid, oscillating between the material reality of an ephemeral urban intervention and the image of an immemorial monument.

|

|

|

| Paulo Bruscky, "Space Art" proposal, published in Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, December 29, 1976. (Click on image to see full page) |

|

Forrest Myers, "Searchlight", 1975. |

|

|

|

| David Antin, "Skypoems", 1987-1988 |

Vik Muniz's contribution to "En el Cielo", 2001 |

The artistic use of skywriting further extended the aerial performances set forth in Futurist manifestoes. In addition to the well-known writings of Futurism's founder, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, of particular relevance is the 1919 manifesto "Futurist Aerial Theatre", by Fedele Azari, in which he wrote: "I HAVE MYSELF PERFORMED, IN 1918, MANY EXPRESSIVE FLIGHTS AND EXAMPLES OF ELEMENTARY AERIAL THEATRE OVER THE CAMP OF BUSTO ARSIZIO. I perceived that it was easy for the spectators to follow all the nuances of the aviator's states of mind, given the absolute identification between the pilot and his airplane, which becomes like an extension of his body: his bones, tendons, muscles, and nerves extend into longerons and metallic wires." Futurist interest for airplanes and aerial performance where largely explored through representational means, most successfully in the works or aeropainter Tullio Crali, whose first actual flight, on a seaplane, took place in 1928. His 1939 canvas "Incuneandosi nell'abitato (In tuffo sulla città)" [Nose Dive on the City] indeed shows a small airplane nosediving towards a nondescript city of skyscrapers as seen from the cockpit. We see the back of the pilot's head but there's no gap separating us from the pilot. The painting does not suggest that the viewer is a passanger. The compressed space aims at vicariously placing the viewer in the position of the pilot and evoking the enthusiasm for aggression and power that characterized Futurism. Rendered in dizzying perspective, the painting has steep angles and dissolving forms, suggesting that at accelerating speed the plane will soon hit the ground (or the buildings). "Incuneandosi nell'abitato" is Crali's most accomplished work and the most emblematic of Futurist aeropaintings. In response to the space race and the moon landing, in 1969 Crali printed and distributed his "Arte Orbitale: Manifesto futurista" [Orbital Art, A Futurist Manifesto]. Alone intriguing for retaining the "Futurist" epithet well into the late 1960s, the manifesto moves Crali's ideas beyond the pictorial realm and proposes plans for artworks that "created in collaboration with scientists and technicians will be placed in orbit around the earth". The manifesto even aludes to the use of "the most advanced techniques" to create "luminous plastic spectacles" competing with "comets aurora borealis rainbows galaxies supernovae" [sic].

Another significant, albeit little known antecedent, is the "Dimensionist Manifesto", published in 1936 by the Hungarian poet Károly (aka Charles) Sirato and signed by Arp, Delaunay, Duchamp, Kandinsky, Moholy-Nagy, and Picabia, among others. The "Dimensionist Manifesto" was published in Paris as a loose sheet attached to the magazine Revue N + 1. Its most ambitious proposal is four-dimensional sculpture: "Ensuite doit venir la creation d'un art absolument nouveau: l'art cosmique (Vaporisation de Ia sculpture, theatre Syno-Sens - denominations provisoires). La conquête totale de l'art de l'espace à quatre dimensions (un "Vacuum Artis" jusqu'ici). La matière rigide est abolie et remplacée par des matériaux gazéfiés. L'homme au lieu de regarder les objets d'art, devient lui-même le centre et le sujet de la création, et la création consiste en des effets sensoriels dirigés dans un espace cosmique fermé." This anticipatory vision would become a reality decades later in multiple ways. One such form was the use of vapors and gases as new art materials, from Robert Barry's "Inert Gas Series: Neon" (1969), in which he documents, with two black-and-white 8-by-10 photographs and a typewritten text, the release of a small amount of neon gas into the landscape around L.A., to the sublime "solid light installations" by Anthony McCall, the first of which ("Line Describing a Cone") dates from 1973. In a room gently filled with mist by a smoke machine, a light beam projects a single bright dot that, in the course of 30 minutes, extends itself into a line that slowly forms the outer skin of a hollow cone.

In 1998 Javier Perez created "Smoke Man", a sculpture in

which a headless male figure gives off periodic puffs of

smoke and in 2002 Pierre Huyghe produced

"L'Expédition Scintillante, Act II: Untitled (light

show)", in which multiple gases are lit by filtered lights

producing a spectacle of evanescent colored forms to the

rythm of music. Another way that gases have been used in

art is through skywriting, as exemplified by "En el

Cielo", an exhibition of skywriting projects created by

several artists for the Venice Biennial in 2001 and

organized by TRANS>, a New York organization that

presents experimental art. In spite of its appeal to

artists, though, skywriting is itself a vanishing art

form, having been largely replaced in the commercial world

by a faster skymessaging technique, known as "skytyping",

in which several planes fly in formation and use a

computer-controlled radio signal to emit puffs of smoke

that form letters. By 2010, be it with laser projection or

computer-controlled smoke emmissions, it could be said

that gases had become a regular contemporary art medium,

as exemplified by works such as "Memory Cloud" (2008) by

Minimaforms , "Trinity Model" (2010) by János Borsos, "For

Those Who See" (2010) by Daniel Schulze, and "Pippen over

Ewing" (2010) by Mitchell Chan.

Bruscky's proposal explored a scale greater than the Land

Art or the Earthworks typical of the period, since his

vision of an artificial aurora borealis would reach

millions at once, who would see the work simply by looking

up at the sky. By contrast, works that manipulate

magnetism or electromagnetism often have a smaller, more

intimate scale. If Takis' work has a forceful and raw

power that emanates from his unadorned handling of

materials such as iron and steel, quite different are the

levitation projects by the American artist Thomas Shannon.

Shannon has been creating since the early 1980s a series

of sculptures based on materials such as bronze, gold, and

marble, as well as painted wood, in which the source of

magnetism is not visible. Rather than seeking to make

evident the tension that results when opposite poles

attract, Shannon's sculptures search for a sense of quiet

equilibrium, resting on the visual harmony created by the

presence of two basic components: the base and the

floating element. Finding in science and natural phenomena

a rich source for visual research, Shannon's vocabulary

takes levitation into the realm of a reduced articulation

of sculptural forms where pairing of objects structures

the magnetic experience.

Many developments in twentieth-century art led to a

radical reduction in the use of physical matter to form

sculptural volume and to support or present this volume in

space. From Gabo's constructions (1919/20) to Fontana's

perforations, from Moholy-Nagy kinetic works to Calder's

mobiles, we have witnessed a movement to liberate modern

sculpture from the constraints of enclosed and static form

resting on the two-dimensional surface of the pedestal.

Artists such as Takis and Shannon -- and the Brazilian

sculptor Mario Ramiro, who in 1986 created a

self-regulating electromagnetic levitator entitled G0

(standing for "zero gravity") -- have given continuation

to this search to release sculpture from gravitropism. In

Ramiro's "Gravidade Zero" (Zero Gravity), an electromagnet

regulated by a photo-sensor maintains a metallic form

floating in space in a state of levitation. Freed from a

two-dimensional base, and from any point of support in

space, this object is in a truly three-dimensional kinetic

space. Ramiro's levitating form presents volume-inversion

relations: The area of the object's greater mass can be

seen at the top. The lower part, the traditional base of

the object, does not need to support the volume above it.

|

|

|

| "Past, Present, Future", 1986,

sculpture by Tom Shannon |

Mario Ramiro, detail of Gravidade Zero (Zero Gravity), wood, brass, glass, electromagnet, electronic components, 81 x 81 x 81 cm, 1986. |

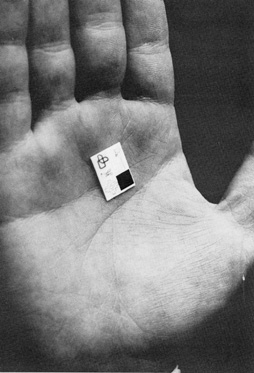

The inevitable conclusion is that zero gravity is the next

frontier. Artworks have been taken aboard spacecrafts

since 1969, when "The Moon Museum", a small ceramic tile

with drawings by artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and

Andy Warhol, was carried to the Moon aboard a Saturn V

rocket on Apollo 12. A significant development was the

permanent installation of a sculpture by artist Paul van

Hoeydonck (Antwerp, b. 1925) on the surface of the Moon in

1971, also carried on a Saturn V rocket on Apollo 15.

Entitled "Fallen Astronaut" (aluminum, 8.5 cm long), the

work was placed at the Hadley-Apennine landing site by

American astronauts Dave Scott and Jim Irwin (Apollo 15).

Next to the sculpture, inserted in the lunar soil is a

commemorative plaque, homage to astronauts and cosmonauts

who lost their lives in the course of space exploration.

In 1989 Lowry Burgess flew objects on the Shuttle as part

of a conceptual artwork entitled "Boundless Cubic Lunar

Aperture". These works are significant steps towards an

art that engages outer space materially, but they were not

created in outer space or conceived specifically to

investigate the new possibilities of art in true

weightlessness. The first works to do so are the sculpture

"S.P.A.C.E.", created outside the Earth by American artist

Joseph McShane in 1984 and the sculpture "The Cosmic

Dancer", created in 1993 by Arthur Woods, an American

artist living in Switzerland.

|

|

|

| Forrest Myers. "Moon Museum", 1969. Miniaturized and iridium-plated drawings on ceramic wafer. | Plate measures 3/4" x 1/2" x 1/40". The drawings are by Myers, Rauschenberg, Oldenburg, Warhol, David Novros, and John Chamberlain. |

McShane's work was launched into space on

October 5, 1984 aboard the U.S. Space Shuttle Challenger.

McShane’s piece was produced with the vacuum of space and

the conditions of zero gravity and returned to Earth in

its altered state. A sphere with a valve and earth

atmosphere within was opened once in orbit. The vacuum of

space evacuated the sphere, the valve was closed, and the

vacuum of space was then contained within. For McShane,

the artwork is not the glass object per se, but the

containment of outer space within, the potential wonder

generated by bringing space vacuum to Earth and to close

proximity to viewers. The question concerning the

reception of space art necessarily involves a reflection

on the experience of it in space. The primary viewers for

"The Cosmic Dancer" lived with the "terrors and pleasures

of levitation" in conditions of zero gravity. A

sharp-angled form launched to the Mir Space Station on May

22, 1993, "The Cosmic Dancer" stressed the cultural

dimension of space since it created the experience of art

integrated into a human environment beyond Earth. The

video that documents the project shows the two Russian

cosmonauts Alexander Polischuk and Gennadi Mannakov

performing (rotating, hovering, flying) with the sculpture

in the confines of Mir, where the sculpture was left. The

flaming remnants of the Mir space station plunged into the

South Pacific on March 23, 2002.

The Cosmic Dancer sculpture on the mir

space station. Space art project by Arthur Woods

launched on may 22, 1993.

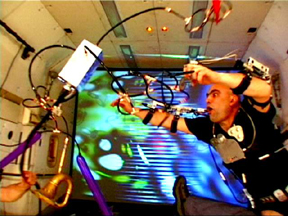

In the case of Arthur Woods, the performance

of the cosmonauts complements his project. As one watches

the video documentation, one feels that the cosmonauts

stand vicariously for all viewers, that is, all those who

in the future will have the opportunity to experience

space as a social and cultural milieu, and not only as a

research lab. Clearly, the performance of the body in an

environment devoid of the forces of gravity is

aesthetically rich in its own right. This very issue has

been the focus of French choreographer Kitsou Dubois's

work for over a decade. Since 1991 she has been flying in

microgravity parabolic flights and exploring the gestural,

kinesthetic and proprioceptive potential of weightless

dance. She has flown alone as well as with other dancers.

Dubois is unique in her relentless investigation of zero

gravity. In addition to continuously pursuing new

levitation opportunities, she has published extensively on

the subject, obtained a Ph.D. with her research as the

topic of the dissertation, and recreated her experiences

in theatrical as well as installation works. As a

byproduct of her choreographic work, Dubois has also

developed a training method for astronauts based on her

new protocols for zero gravity dance.

The spectrum of the live arts in space would be incomplete

without theater. In 1999 Slovenian director Dragan

Zivadinov staged his Noordung Zero Gravity Biomechanical

Theater high above the Moscow skies, onboard a cosmonaut

training aircraft. The flight crew consisted of fourteen

people: six actors and an audience of eight. A series of

eleven airborne parabolas, with gravity changes

oscillating from normal, to twice the usual, to 30-second

microgravity episodes, is not the most conducive temporal

structure for a long dramatic play. This posed no problem

for director Zivadinov, whose vision of an abstract

theater is well matched by the experience of

weightlessness. Zivadinov placed a red set on the back of

the plane and seats for the audience of eight on each wall

of the aircraft. Launched from the stage into the empty

space before it, actors wearing brightly colored costumes

performed in a state of levitation, before being pushed

down to the floor by gravity changes, and back up in the

air again, and so on, as the airplane completed its

parabolas. After eight parabolas, Zivadinov allowed the

audience to leave their seats and participate in the

euphoric state of bodily suspension, a unique form of

audience-actor empathy and, undoubtedly, a new level for

the old-age dramaturgical device once described by

Aristotle as catharsis.

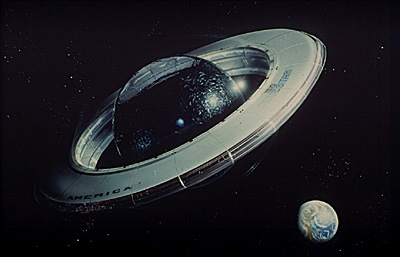

While Zivadinov conceived of the aircraft as a theatrical

set, and Woods employed a space station as an ancillary

element in the fulfillment of the antigravitropic

potential of his sculpture, the media artist, architect,

and designer Doug Michaels proposed in 1987 the design of

a rather unique space station cum artwork cum "alternative

architecture". A co-founder of Ant Farm design group

('68-'78), Michaels was the co-creator of emblematic works

of the period, such as Cadillac Ranch (ten cars planted

nose down in 1974 in a wheat field located west of

Amarillo, Texas) and Media Burn (a 1975 performance in

which Michels drove a Cadillac through a pyramid of

television sets on fire). In 1986 he established the Doug

Michels Studio to pursue innovative projects in

architecture and design. Michaels, who passed away in

2003, developed with his colleagues in 1987 a concept for

a spacecraft to host artists and scientists interested in

human-dolphins interaction and communication. The project

resonated with the pioneering work of John Lilly, a

scientist who defended the idea that dolphins have

consciousness and intelligence at a time when this fact

was not yet scientifically established. As a result of his

research, Lilly went on to author books such as "Man and

dolphin" (Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday, 1961), "The Mind

Of The Dolphin: A Nonhuman Intelligence" (Garden City,

N.Y., Doubleday, 1967) and "Communication Between Man and

Dolphin: The Possibilities of Talking With Other Species"

(New York: Crown Publishers, 1978). On its

January-February issue of 1987, the magazine The Futurist

featured Michaels's Project Bluestar, an orbiting "think

tank in zero gravity" meant to include both humans and

dolphins. According to the proposed design, the marine

mammals' ultrasonic emissions would be used to program the

central computer. This proposal was as much about the

vision

|

Detail Detail |

|

|

Doug Michels, "Blue Star Human Dolphin

Space Colony", 1987. Artwork by Peter

Bollinger. |

In 1993, the same year Woods launched "The

Cosmic Dancer", the Chinese artist Niu Bo started "The

Zero-Gravity Project", which he first pursued in Japan

with a plane that flies in parabolic arcs at 20,000-25,000

ft. Bo covered the interior of the plane with rice paper

and used a paint produced from the mixture of several

elements. To create this paint the artist combined China

ink, watercolor, and oil, among other materials, and

placed the paint in balloons. During the near

weightlessness of microgravity flights, he released the

paint. With his "Space Atelier" Bo wishes to convey that

just as the Impressionists had to leave their studios to

explore the possibilities of natural light, a new culture

will be created when artists leave the surface of the

Earth.

Niu Bo, The Zero-Gravity Project, 1993.

The Spanish artist and performer Marcel.li

Antúnez Roca created Dedalus, a series of

microperformances realized in 2003 during two parabolic

flights aboard the Tupolev plane, flown at the Gagarin

Cosmonaut Training Center, Star City, Russia. This work

was part of a larger project carried out by the London

organization The Arts Catalyst, which aims to enable

artists to work in microgravity conditions. Performing

with an exoskeleton wireless interface and the robot

Requiem, Roca's involuntary movements activated videos by

means of potentiometers in the dresskeleton’s circuit. The

videos explore themes that the artist considers evocative

of an exobiological iconography, such as

biochemistry/microbiology, higher transgenic organisms and

bio robots.

|

|

Marcel.li Antúnez Roca, Dedalus, 2003

Artworks such as discussed above open a new

realm of speculative inquiry into the future of art in

worlds other than the Earth. While we remain confined to

the blue planet, three possibilities open up for art that

engages what could be called a "zero gravity sensibility".

First, it is clear that the potential for magnetism and

electromagnetism in art is far from exhausted. Second, the

increasing access to microgravity facilities in Russia

will force the opening of new markets in Europe, Japan,

and the United States, further enabling more artists and

performers to explore weightlessness. Third, as plans for

space tourism evolve, actual zero gravity might also

become more accessible, albeit at a lower pace, since

costs will remain high for the foreseeable future. Space

tourism was jumpstarted on April 28, 2001, when the

Russian Soyuz-U booster blasted two Russian cosmonauts and

a paying tourist, the American millionaire Dennis A. Tito,

into orbit for a rendezvous with the International Space

Station.

Electromagnetism holds great potential for sculptural

levitation. Yet untapped, for example, is a property known

as diamagnetism. Diamagnetic materials repel both the

north and south poles of a magnet. All materials are

weakly diamagnetic, but it is difficult to levitate

ordinary objects. However, with a strong magnetic field

and strongly diamagnetic materials (such as neodymium

magnets and graphite blocks), it is possible to create

stable regions for diamagnetic levitation.

Artists seeking to explore levitation beyond magnetism and

electromagnetism can investigate advanced techniques

presently only found in research laboratories. A

high-temperature electrostatic levitator allows the

control of heating and levitation independently and,

unlike an electromagnetic levitator, does not require that

the floating object be a conductor of electric charge.

Acoustic levitators enable the suspension of liquids in a

state of equilibrium through acoustic radiation force.

Also, liquids can be suspended by a gas jet and stabilized

by acoustic forces. Superconductor levitators enable

objects to float above a magnet in fog of liquid nitrogen.

With a laser levitator it is possible to trap gas bubbles

in water and create a condition of stable levitation by

applying optical radiation pressure of the light beam

horizontally and vertically. Atom chips allow for the

trapping and manipulation of clouds of atoms, which

magnetically levitate above the chip's surface. Portable

quantum labs promise to further expand the magnetic

control of atom clouds levitating in free space. At last,

as levitation touches biology, molecular magnetism is

predicated on the application of ordinary but very strong

magnetic forces over a regular object. The forces are

directed upwards and take advantage of the very weak

magnetic response of the object present in the field,

enabling the levitation of objects usually not regarded as

capable of levitation (such as plastics) and living

organisms (plants, insects, small animals -- and

conceivably humans, if the field could be made strong

enough). The manipulation of the magnetic properties of

nanosized objects is also a possibility, which could

include macroscopic manifestation of the quantum behavior

of these very small objects. Since levitation depends only

on the dielectric properties of the various materials, if

vacuum is replaced by certain media (such as fluids)

quantum mechanical energy fluctuations would generate an

attractive force between objects that are very close to

each other. Thus, quantum levitation of objects in a fluid

emerges as another practical direction for aesthetic

research. Further developments in quantum levitation make

it clear that astounding levels of control can be

achiveved when superconducting materials are sandwiched

between layers of gold and sapphire crystal and dipped

into liquid nitrogen at minus 300 degrees Fahrenheit. In

this case, when one manipulates levitating objects and

changes their orientation, the objects retain their new

position with absolute stability. Possibilities

proliferate with pseudo-magnetic fields created with

graphene stretched to form nanobubbles on a platinum

substrate, or real laser "tractor beams," that can move

very small particles or microbes. The latter is achieved

through a hollow laser beam with a ‘dark core.’ One side

of the particles (which are trapped in the 'dark core')

remains in darkness while the other is illuminated by the

laser, thus pushing the particles along the hollow laser

conduit. In a closed container, it is possible to use

vibrations to make objects and particles float under a

levitating layer of liquid, which remains aloft on a

cushion of air. The vertical shaking of liquids can

stabilize unstable systems and produce buoyancy on the

lower side of the liquid, thus behaving as if the

gravitational force were inverted. These techniques offer

a glimpse into the new artforms that might emerge when

life in the international space station becomes more

common, when colonization of the Moon goes from science

fiction to science fact, and when the space program

overcomes what, in the public opinion, is its most

exciting challenge: landing human beings on Mars. The

creation of new alloys and compounds in zero gravity, the

continuous discovery of new optical and subatomic

behaviors and the prospect of interplanetary colonization

suggest that levitation and space exploration are more

than a metaphor in art. They constitute a material and

intellectual challenge that must be met.

NOTES

1 - Gravitropism is a Botany term. Roots have positive

gravitropism because they grow in the same direction of

gravitational forces (i.e. down). Stems on the other hand

have negative gravitropism, as they grow against gravity

(i.e. up).

2 - Kac, Eduardo. "Sintaxe, Leitura e Espaço na

Holopoesia", catalogue of the exhibition "Arte e Palavra"

(Word and Image), Forum de Ciência e Cultura, Universidade

Federal, Rio de Janeiro, 1987.